Understanding Leap Year History and Purpose: Ancient Origins to Modern Celebrations

The Ancient Adjustment of Time

Long before the advent of modern calendars, ancient civilizations grappled with the challenge of aligning their time-keeping systems with the solar year. The Earth’s orbit around the Sun takes approximately 365.25 days, a fact that necessitated periodic adjustments to ensure that calendars remained in sync with the seasons.

The ancient Egyptians were pioneers in solar calendar development, recognizing the need for an extra day every four years by the 3rd century BCE. This early leap year concept, although not termed as such, was a significant step towards more accurate timekeeping.

The Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BCE, formalized the leap year in a way that closely resembles our modern understanding. Advised by the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes, Caesar’s reform added an extra day to February every four years, compensating for the quarter-day discrepancy between the calendar year and the solar year. This innovation was crucial for realigning the Roman calendar with the seasons after years of lunar calendar misalignment.

Leap Year in Diverse Cultures

Beyond Rome, other civilizations devised their methods to account for the solar year’s length. The Mayan calendar, known for its complexity and accuracy, used an intricate system to track solar, lunar, and planetary cycles, though it did not include a leap year in the Julian sense. Instead, the Mayans’ advanced astronomical observations allowed them to predict celestial events with remarkable precision.

The Chinese calendar, a lunisolar system, introduced leap months approximately every three years to maintain alignment between lunar months and the solar year. This adjustment ensured that agricultural and cultural practices remained in harmony with seasonal changes.

Similarly, the Babylonians added intercalary months as determined by priests, based on agricultural cycles and celestial observations, showcasing an early understanding of the need for calendar correction.

Celebrations, Myths, and Legends

Leap years today are less about the technical necessity of calendar alignment and more about the cultural and social traditions that have arisen around this quadrennial occurrence. One of the most charming traditions is that of women proposing to men on February 29th, a practice with roots in Irish legend. It is said that St. Bridget struck a deal with St. Patrick, granting women this right every leap year to balance traditional gender roles.

This tradition also carries the quirky custom that if a man refuses such a proposal, he owes the woman a penalty, ranging from a kiss to a silk dress. Such customs add a layer of folklore and fun to the leap year, enriching its cultural significance.

Some cultures celebrate leap day with special events and festivals. For example, the town of Anthony in Texas/New Mexico, USA, declares itself the “Leap Year Capital of the World”

Leap years have also been shrouded in superstitions and myths. In some cultures, leap years are considered inauspicious for farming, weddings, and other significant life events. However, these beliefs contrast sharply with the leap year’s practical origins and its essential role in keeping our calendar in alignment with the Earth’s orbit.

Leap Year by the Numbers

A leap year is a year containing one additional day added to keep the calendar year synchronized with the astronomical or seasonal year. This extra day is added to February, making it 29 days long instead of 28. Leap years occur almost every four years. The exact rule is that a year must be divisible by 4. However, if the year can be evenly divided by 100, it is not a leap year unless it is also divisible by 400. Therefore, 2000 was a leap year, but 1900 was not.

The current system of leap years was established by the Gregorian calendar, introduced in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII. This replaced the Julian calendar, which had a simpler leap year rule that eventually led to a significant drift from the solar year. If the leap year rule was not used, our calendar would have shifted about 110 days shifting our dates and entire season. This would make New Years start on April 20th.

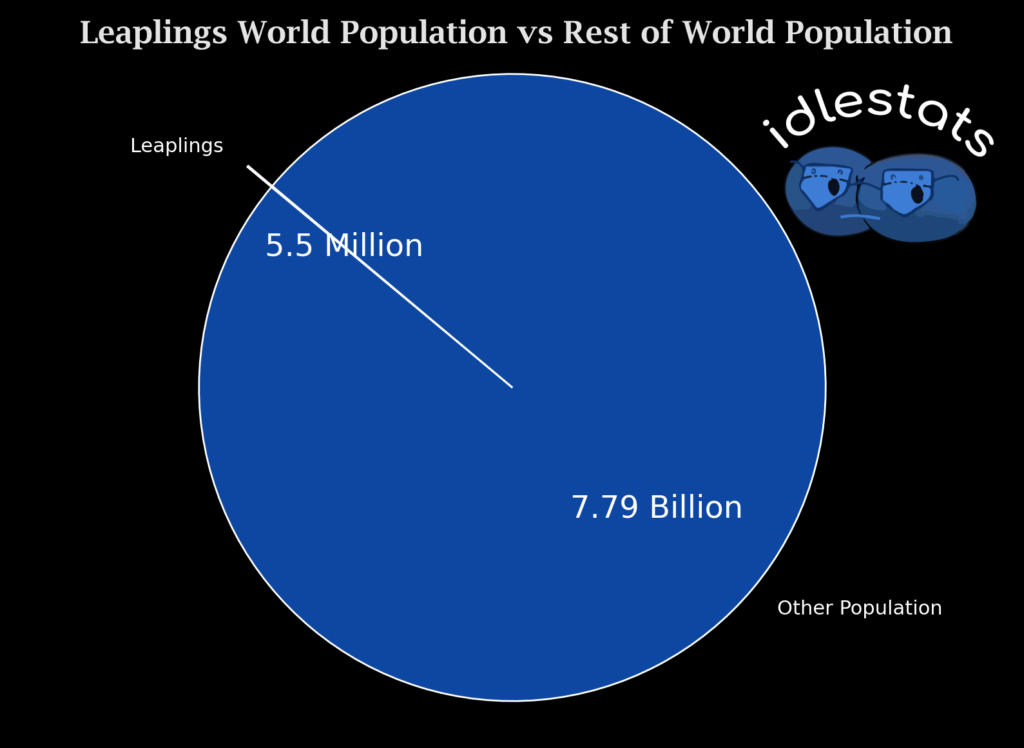

People born on February 29 are often called “leaplings” or “leapers.” They typically celebrate their birthdays on February 28 or March 1 in non-leap years, though some may celebrate their birthday only every four years. There are approximately 5.5 million Leaplings in the world which is about the same population of Norway.

Conclusion

From ancient Egyptian astronomers to modern-day leap day proposals, the leap year remains a fascinating intersection of astronomy, culture, and history. It serves as a reminder of humanity’s ongoing quest to understand and organize time, a pursuit that has led to the creation of complex calendars and rich traditions. As we continue to celebrate leap years, we honor both our scientific heritage and the cultural practices that bring color to our lives.

Other Articles

Sources

What Is a Leap Year? | NASA Space Place – NASA Science for Kids